- November 2025

Satellite imagery can offer a powerful new perspective on the drivers of climate displacement, as case studies in Ghana and Libya demonstrate, but ethical concerns and data limitations call for caution, especially amid advances in digital technology.

Climate shocks and hazards are rapidly reshaping forced displacement trends in Africa, with the continent expected to see as many as 105 million people migrating in the context of climate change by 2050.[1] Good data will be needed to assess and monitor climate displacement, and evaluate interventions designed to rebuild communities and livelihoods. This requires context-specific approaches that combine field-based methods with new forms of data, such as satellite imagery. The two case studies in this article illustrate the power of satellite imagery to shed light on the drivers of climate displacement and to help to inform responses.

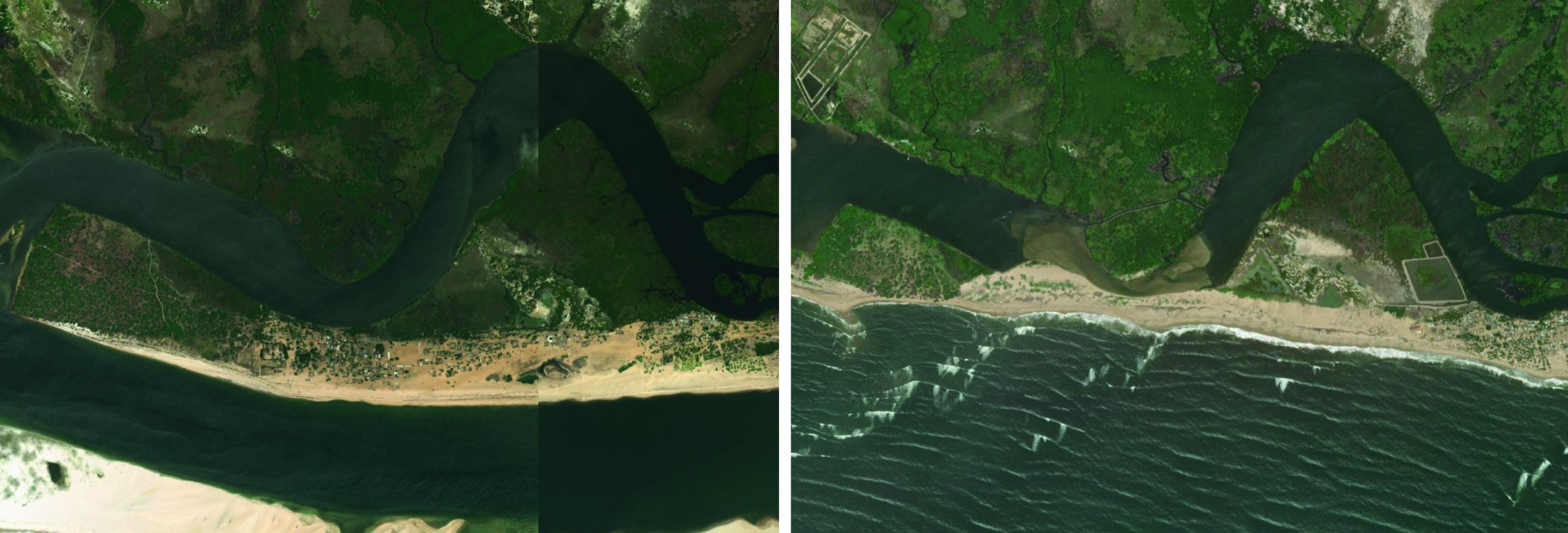

Coastal erosion in Ghana

Fuveme is a coastal community situated in the Anloga District of Ghana’s Volta Region. It is located east of the Volta estuary, which has become increasingly vulnerable to sea-level rise and associated flooding. Between 2005 and 2017, a combination of satellite imagery and drone technology revealed that 37% of Fuveme’s coastal land had been lost to coastal erosion and rising sea levels.[2] As part of the broader Volta Delta ecosystem, the area is endowed with valuable natural resources, including minerals, wetlands, lagoons, groundwater and fish stocks. These resources form the basis of the local economy, with most residents engaged in fishing and fish-related activities.

Figure 1 (see above) contains satellite imagery of the impact of coastal erosion on Fuveme taken in March 2017 and May 2025. The image from 2017 depicts the shoreline prior to the intensified effects of sea-level rise in the area. At this point, the coastline appears relatively intact, with a broader landmass that suggests the presence of a wider beachfront. There is evidence of built infrastructure near the water’s edge, alongside natural coastal features such as vegetation and sandbars, among others, which serve as natural buffers that would be expected to protect the area from further coastal erosion.

By contrast, the image from May 2025 reveals notable alterations in the coastal landscape. The shoreline has receded significantly inland – by several meters in some locations – which can be attributed to climate change in the region. This indicates a marked increase in coastal erosion and tidal flooding. Land areas visible in 2017 have since been submerged, and several buildings and structures previously located near the sea appear to have been destroyed. Additionally, the loss of vegetation along the coast reflects the erosion of natural coastal defences, further exposing the area to high-energy wave activity and storm surges.

Taken together, the two satellite images provide a good visual narrative of the ongoing environmental degradation in Fuveme over an eight-year period. These images not only show physical changes in the coastal zone; they also have significant implications for destruction of livelihoods, cultural loss and displacement. Indeed, subsequent field visits have revealed there is now no trace of a once-thriving community of roughly 1,000 people.[3] Many of the displaced residents were relocated further inland to a new settlement called Fuveme-New Town, but fishing and fishmongering continue to be the community’s traditional sources of livelihood, compelling residents to return to the coastal ecosystem with which they are familiar for economic survival.[4] Such cultural connections and economic practices cannot easily be reestablished by relocation methods.

Nevertheless, opportunities for the innovative use of satellite imagery that incorporate local considerations look promising. In the White Volta Basin, another region of Ghana, integration of satellite imagery with participatory mapping improved flood mapping accuracy, enabling more reliable risk assessments and early warnings.[5] Participatory mapping engaged local communities, combining their knowledge with satellite data to delineate flood-affected areas. This process empowered communities and ensured that interventions addressed locally prioritised needs.

Flash flooding in Libya

Derna is a coastal city located in eastern Libya along the Mediterranean shoreline between the Jebel Akhdar mountains and the sea. Throughout its history, Derna has benefitted from its strategic location with access to natural resources such as fertile soils, freshwater springs and rich marine ecosystems. These resources underpinned local livelihoods, with many residents relying on small-scale agriculture, trade and fishing as primary sources of income. However, Derna is also highly vulnerable to flash flooding due to its position at the mouth of Wadi Derna, a seasonal river valley that channels fresh rainwater into the city. Dams upstream of the city held millions of gallons of water from rainfall until 11 September 2023, when Storm Daniel hit the eastern Libyan coastline, resulting in the dams’ collapse and the single deadliest flooding event in Africa. [6] The fragmentation of the Libyan state as a result of the Libyan civil war greatly impacted the dams’ structural integrity. According to reports, corruption and mismanagement of funds meant that the dam was not adequately maintained. [7] Over 23,500 people and 4,700 households were displaced internally within Derna.[8]

Figure 2: Derna, Libya (Left, 2022; Right, 2024). Source: Esri, DigitalGlobe, Maxar, and the GIS User Community

Figure 2 contains satellite imagery of the impact of Storm Daniel on Derna taken in October 2022 and November 2024. The second image depicts Derna in the aftermath of the storm showing the scale of the destruction; buildings previously visible are no longer to be seen, swept into the sea by the water’s force.

Satellite imagery was crucial for relief efforts. International organisations used it to identify which neighborhoods in Derna had lost the most housing, roads and water infrastructure, helping authorities to prioritise where to deploy emergency shelter and restore services and where to begin reconstruction.[9] Humanitarian agencies also used geospatial mapping with local partners to guide the placement of aid distribution points and temporary resettlement areas, ensuring assistance reached displaced households most in need.

The changes in satellite imagery thus provide insight into social and economic realities. It is hard to downplay the role of the climate in displacing entire communities when images make the scope and scale of the changes in the area so clearly visible. Frontline responders, other relevant stakeholders and the general public can use accessible digital tools, such as EU’s Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem, NASA’s Earth Science Data System, the crowdsourced OpenStreetMap, and the open-licensed OpenAerialMap, to show the extent of continuing damage in their own communities. In sudden-onset situations, having the most up-to-date, high-definition images can make a difference when assessing situations.

However, there are limitations in data access and quality. More resources are needed to enable coordination and communication between frontline responders, local community members and international organisations, and for the analysis of prolonged environmental exposure. Resources are also often unavailable in the countries and areas where they are needed most.

The road ahead

Satellite imagery as a digital tool offers the potential to monitor and develop plans to better address the effects of climate change, and thus climate displacement, on affected communities. With increased access to open source satellite data, satellite imagery can be used to add nuance to understandings of climate displacement in different contexts in both slow and sudden onset climate-related hazards as the case studies illustrate. However, there are several considerations for practitioners to note in the future.

Ethics and data privacy concerns

As satellite imagery becomes more accessible and widely used in addressing climate displacement, it is critical to remain aware of the ethical dimensions and data privacy concerns associated with its application. The use of high-resolution imagery to track environmental changes or population movements – however well-intentioned – may inadvertently expose vulnerable communities to surveillance or exploitation. This is particularly concerning in contexts of forced displacement, where affected individuals and groups often lack the power to consent to, or challenge, how data about them is collected, interpreted or disseminated. Use of satellite imagery must be guided by ethical principles that prioritise data privacy and protection, ensure informed engagement wherever possible with local experts and safeguard against the misuse of spatial and personal data. Collaborations with local actors and affected populations are essential.

Scarcity and unreliability of field-based data

While satellite imagery offers valuable insights into climate displacement, its effectiveness is significantly enhanced when integrated with accurate field-based data.[10] However, in many regions across Africa, field data remains scarce, outdated or inconsistent, limiting the accuracy and relevance of analyses. The lack of comprehensive figures on displacement – particularly for marginalised subgroups among forcibly displaced populations– compounds this challenge. Such gaps may lead to the exclusion of vulnerable populations from policy responses or programmatic interventions or lead to the misallocation of resources. Improving the quality, frequency and inclusivity of field data collection should therefore remain a priority for governments, humanitarian organisations and research institutions in order to take full advantage of satellite imagery. Community-based participatory approaches that centre lived experiences can complement satellite observations, offering a more holistic understanding of climate displacement. Satellite tools should be seen as a complement – not a substitute – for on-the-ground engagement.

The advent of advanced digital technologies

The future of satellite-based approaches in climate displacement analysis lies in their integration with emerging digital technologies. Machine Learning (ML) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) are increasingly being used to automate the detection of environmental changes, identify risk patterns and predict future displacement scenarios. These advances hold great promise for scaling early warning systems, enhancing real-time monitoring and supporting anticipatory action. However, the successful implementation of these technologies relies on foundational knowledge of satellite-based methods, as showcased in this article. Before practitioners can fully leverage AI or ML-driven insights, there must be a clear understanding of how satellite data is sourced, interpreted and validated. Without this grounding, there is a risk of overreliance on automated systems that may replicate existing biases or misinterpret contextual nuances.

As governments, humanitarian organisations and research institutions increasingly adopt advanced digital skills in addressing forced migration, we call for this adoption to be accompanied by investments in satellite-based methods training, accessible education and capacity-building and digital literacy, especially among practitioners and communities in the Global South. Equipping local actors with the foundational knowledge needed to engage meaningfully with geospatial data can help ensure that advanced digital technologies complement – rather than replace – human expertise and agency.

By addressing these key challenges, the humanitarian and development sectors can harness the full potential of satellite imagery to inform just and effective responses to climate displacement.

Sarah Hoyos-Hoyos

Research Technician – Data Science, Canada Excellence Research Chair in Migration and Integration program, Toronto Metropolitan University, Canada

sarah.hoyoshoyos@torontomu.ca

linkedin.com/in/sarah-hoyos-hoyos

Yousef Khalifa Aleghfeli

Research Fellow – Data Science, Canada Excellence Research Chair in Migration and Integration program, Toronto Metropolitan University, Canada

yousef.aleghfeli@torontomu.ca

linkedin.com/in/yksbs

Emmanuel Kyeremeh

Assistant Professor, Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, Toronto Metropolitan University, Canada

ekyeremeh@torontomu.ca

linkedin.com/in/emmanuel-kyeremeh-222a6a1a

[1] Clement V, et al (2021) Groundswell Part 2: Acting on Internal Climate Migration, World Bank

[2] Usman IK (2025) Eroding homes: Ghana’s disappearing coastal communities, PreventionWeb, United Nations Office of Disaster Risk Prevention

[3] See endnote 2

[4] Kutor SK, Ofori OD, Akyea T and Arku G (2025) ‘Climate change-immobility nexus: perspectives of voluntary immobile populations from three coastal communities in Ghana’, Climatic Change, Vol 178 (2): 14

[5] Li C, et al (2022) ‘Increased flooded area and exposure in the White Volta river basin in Western Africa, identified from multi-source remote sensing data’, Scientific Reports, Vol 12 (1): 3701

[6] Nemnem AM, et al (2025) ‘How extreme rainfall and failing dams unleashed the Derna flood disaster’, Nature Communications, Vol 16 (1): 4191

[7] Joseph M (2025) ‘Brief notes on Derna, Libya: Climate, corruption, displacement’, Cultural Dynamics, Vol (3): 231-35

[8] International Organization for Migration (2023) Libya — Impact of Storm Daniel: Displacement and Needs Update: Derna Municipality

[9] World Bank (2024) Libya Storm and Flooding 2023: Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment

[10] Burke M, Driscoll A, Lobell DB and Ermon S (2021) ‘Using satellite imagery to understand and promote sustainable development’, Science, Vol 371 (6535): eabe8628

READ THE FULL ISSUE